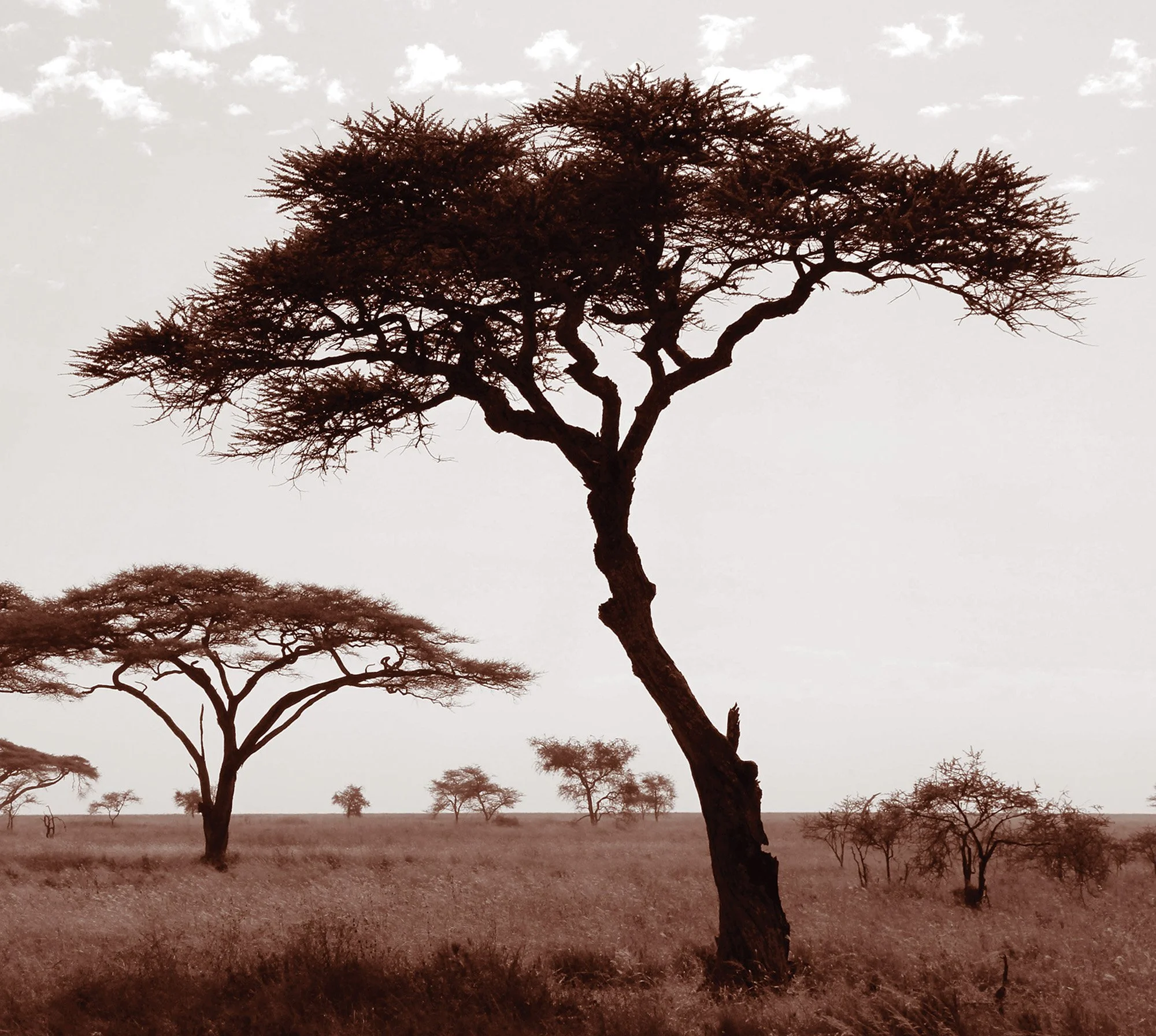

Africa Series

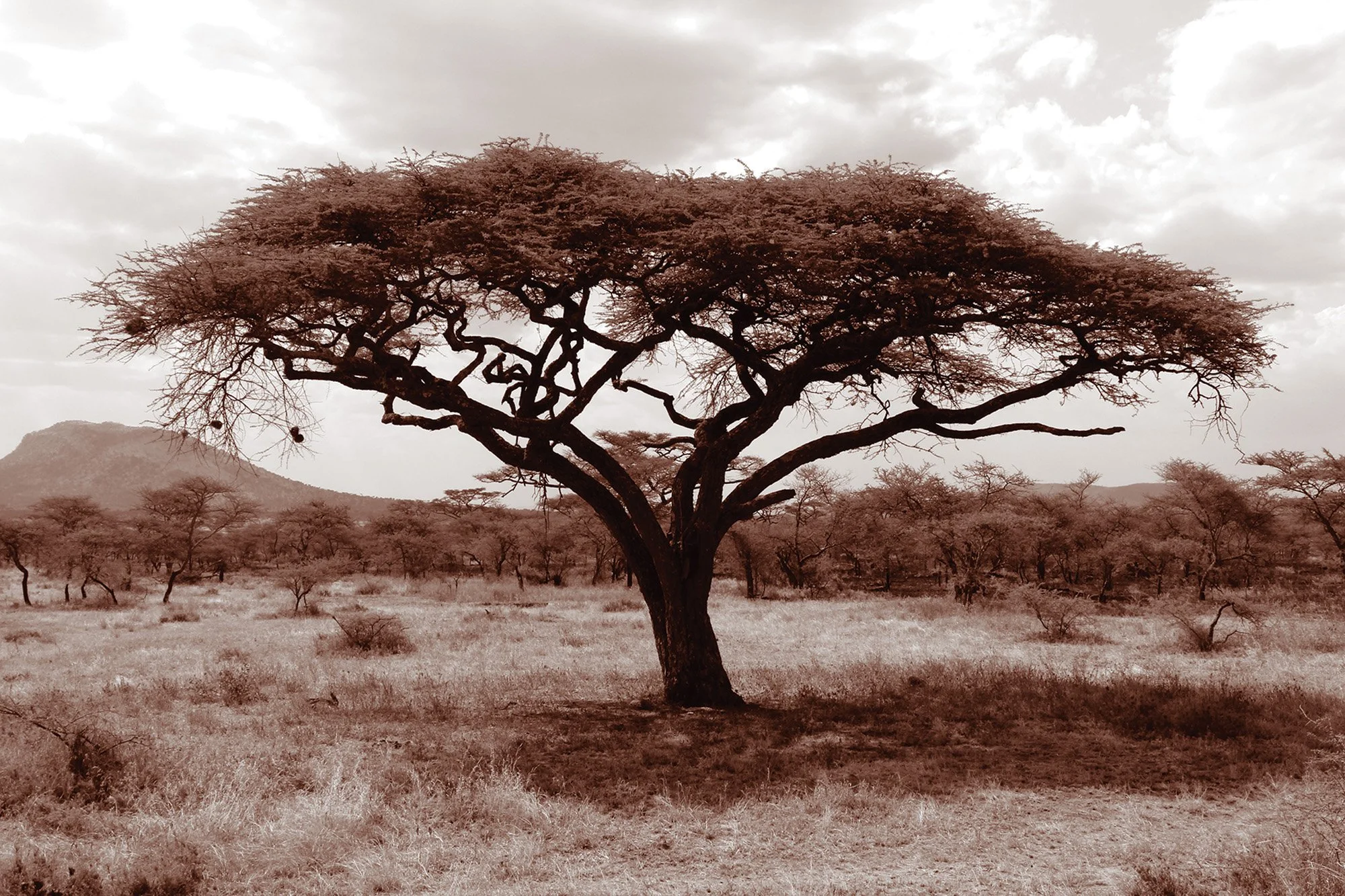

Grand foliage of the Serengeti.

Serengeti Tree 2

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

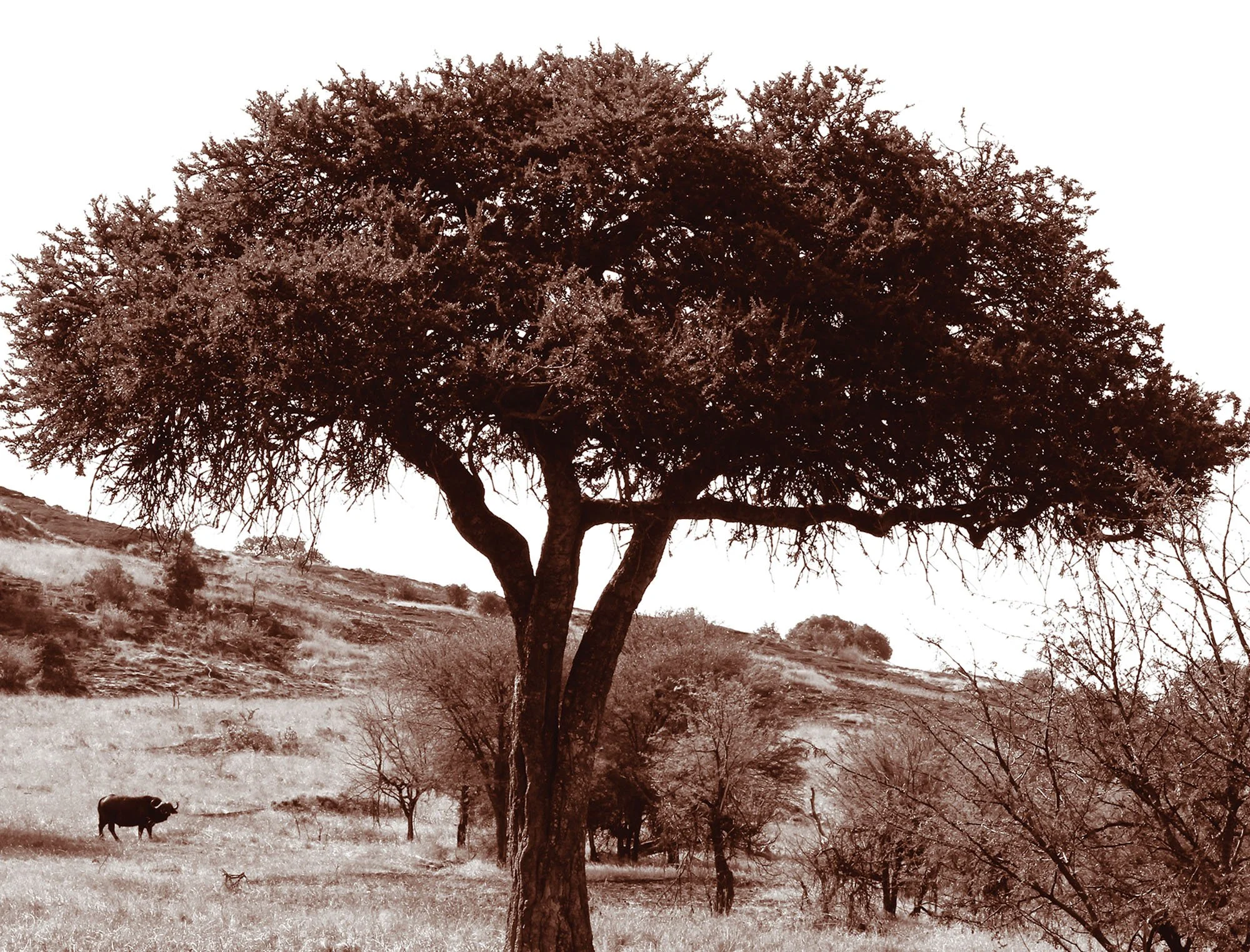

Serengeti Tree 3

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

Serengeti Tree 4

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

Serengeti Tree 5

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

Serengeti Tree 6

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

Serengeti Tree 7

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

Serengeti Tree 8

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

Serengeti Tree 9

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

Serengeti Tree 10

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

Serengeti Tree 11

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

Serengeti Tree 12

Archival pigment print on Arches 140 lb.

cold press watercolor paper

16" x 16" each

Printed in an edition of 10

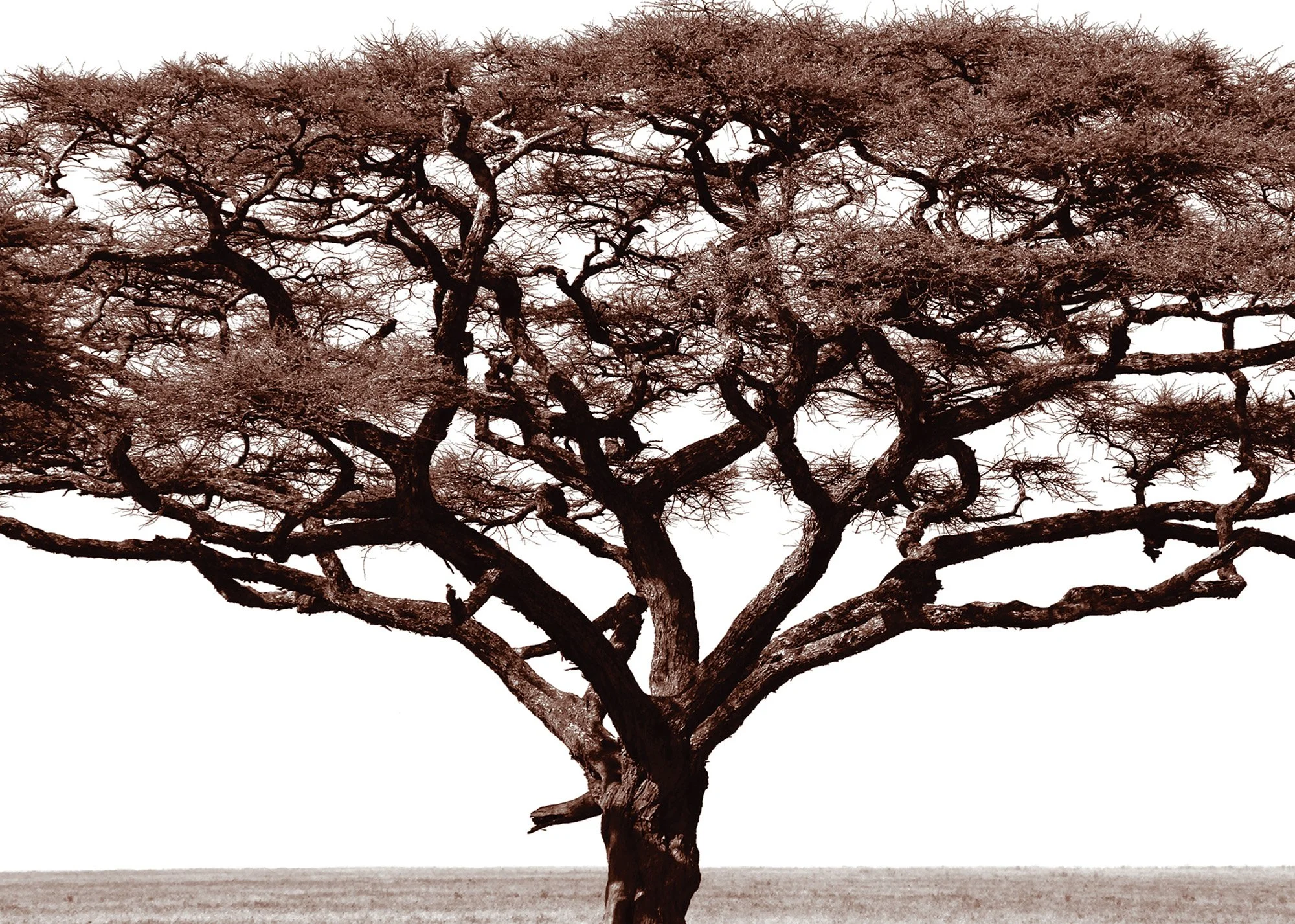

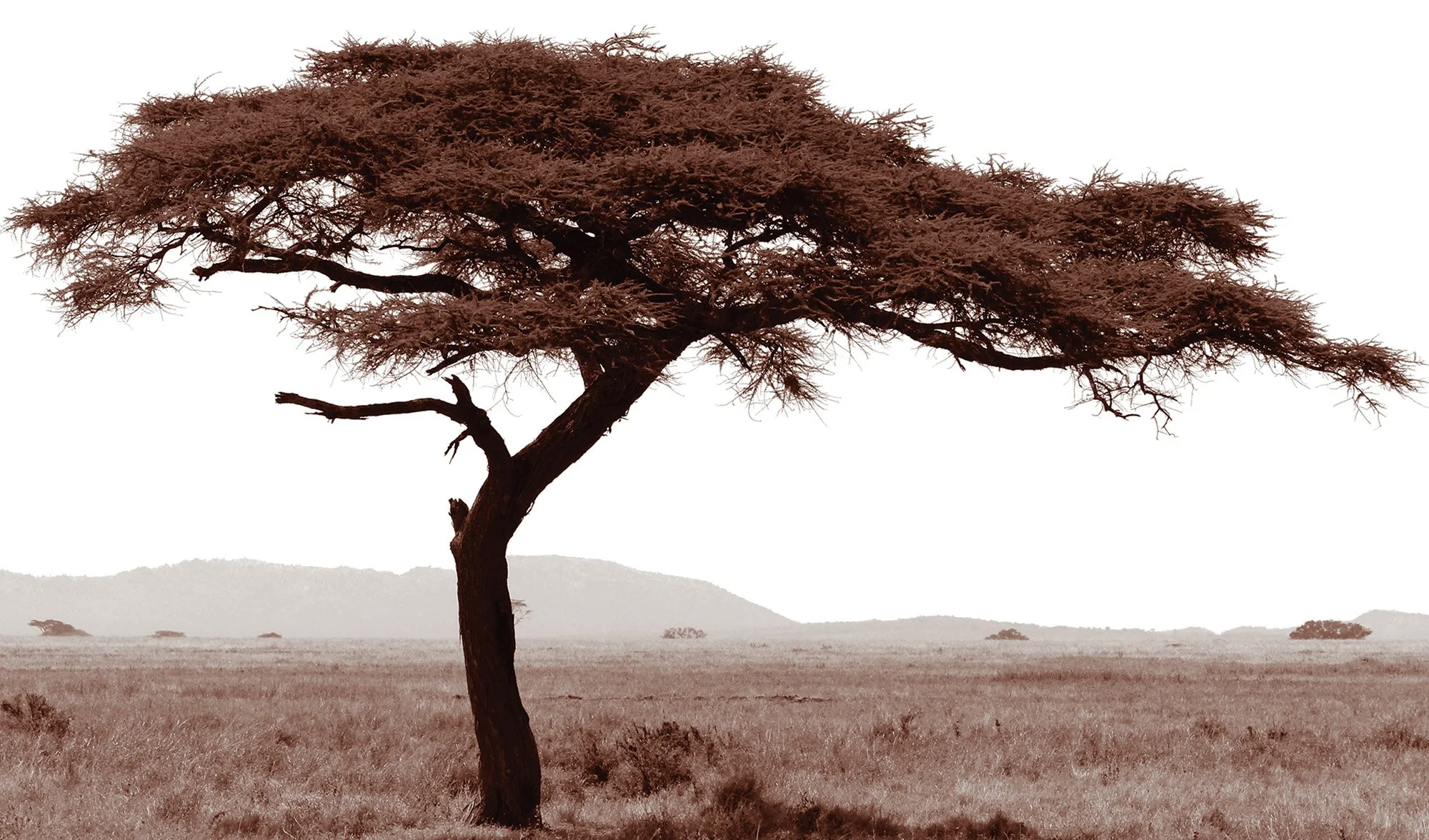

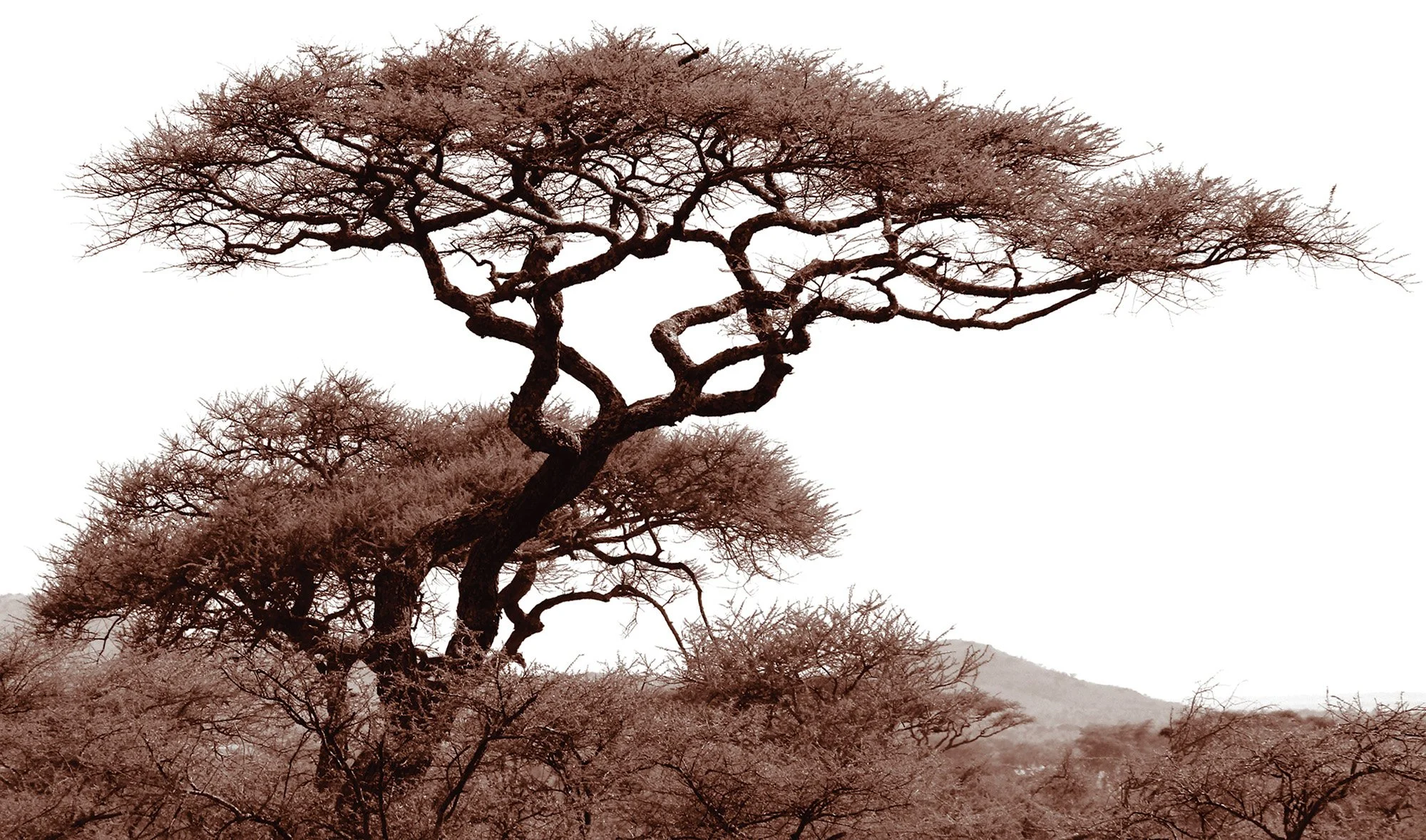

In some photographs, Brown strips down the tree to a simple black silhouette against pure white. His other approach is even more appealing: subtly detailed images of trees amid the savanna, using a sepia tone that makes them look like they came from the 19th century.

—Louis Jacobson, Washington CityPaper

There is a reawakening of one's senses during travel through Africa. Exotic spices (such as cardamom, cinnamon, turmeric, and ginger) fill the air, along with melodic calls from various animal species that roam the plains of the Serengeti. The visual landscape ranges from arid to tropical, urban to rural.

While exploring the African Savannah in 2013, the grand, sculptural qualities of the foliage (including Acacia, Sausage, Balanites [Desert Date], Umbrella, Baobab, Almond, Tulip, and Palm) captured a significant portion of my attention. These monumental structures project broad canopies that provide desirable shade and shelter for wildlife. In other cases the hardwoods produce vivid flowers, nuts, and succulent fruits to nourish the creatures that roam through the extraordinary ecosystem.

The earth's rich, red soil often covers the timbers' entire limbs with a coating of thick dust as a result of wind storms that blow across the flat, open fields. In other habitats, the lush and densely-leafed branches shimmer in the bright, yet unforgiving, sunlight.

Densely populated forests are rare, except in higher altitudes—such as the Ngorongoro Crater. In most environments, the trees stand apart regally, almost in a solitary manner. Quite often, their imposing stature reflects hundreds of years of growth (in a single plant!).

Yet, these structures are vulnerable, too. Thick and heavy branches could be removed or an entire tree might be leveled by herds of elephants in search of berries that are available only on higher branches. In addition, wildfires can sweep away all plant life for several miles—leaving the evidence of devastation.

Nevertheless, nature evolves and finds ways to ensure new growth will replace what had existed beforehand.

The trees of the Serengeti compelled me to photograph their majestic, fragile, and enduring beauty.

Image: Out of Africa, Installation View, Cross Mackenzie Gallery, Washington DC, 2014